Louisiana (Manyflower) Broomrape - Orobanche ludoviciana subsp. multiflora

Louisiana (Manyflower) Broomrape

Percha Box, East of Hillsboro, New Mexico, USA

August 2, 2015

Sometimes a chance encounter can take you aback and cause a moment of reflection. That happened to me on August 2 of this year as I walked near the Percha Box, east of Hillsboro. I had been walking in the stream bed, jumping across the rivulets of water when I could and wading across when I could not. It had been raining all afternoon in the Black Range to the west and the falling water was getting closer and I was afraid that the running water that would go with it might be coursing down the creek at this very moment. Up on the bank I went, walking along a cow path and there in the sandy soil, on a bank that could wash away in any high water event, was a Manyflower Broomrape, Orobanche ludoviciana subsp. multiflora. Just as I started to take photographs of the Broomrape and its sibling nearby, the rain came, my hat came off to cover the camera and hat and camera went under my shirt for added protection. Then I trudged off up the stream, bent over to provide a bit more protection for the electronics, water streaming off the end of my nose.

As I walked along the stream, I mulled the life of a parasite - I’m not talking politics here. In many ways it is a difficult way to exist, the parameters of existence are so strongly defined by another being. When I am wet and slogging through sand and water I am prone to think about such things, I mean, no one else will... Well, in this case Artemisia carruthii (Carruth’s Sagewort or Sagebrush) which is a primary host of this broomrape, seems to be doing okay.

The common name of this species is Louisiana Broomrape (it is also the name of the nominate subspecies), as opposed to Manyflower Broomrape which is the name of the subject subspecies - there are only two subspecies. The range of the Louisiana Broomrape is more-or-less limited to the western part of the continent. Dark green means it is native and present in the state or province; light green means it is native and not rare in the county; and yellow means it is native and rare in the county. Brown, well brown means you ain’t got no luck at all - it isn’t there. Its range extends south into Mexico.

The second range map is from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and shows the range of the subject subspecies. O. l. multiflora was initially described by James Nuttall, as Myzorrhiza multiflora, it now has several scientific synonyms. Both subspecies are found in New Mexico so it is not possible to parse the subspecies range from the first map.

Some people have roasted the roots and young stems of this species to eat and it has been prepared and used as a dressing for wounds and a treatment of ulcerated sores. In this case, especially, care should be taken before eating or using this plant. Parasitic plants absorb a variety of substances from their host (in this case, members of the Aster family in general and the genus Artemisia specifically), creating a substantial uncertainty about toxicity (among other things).

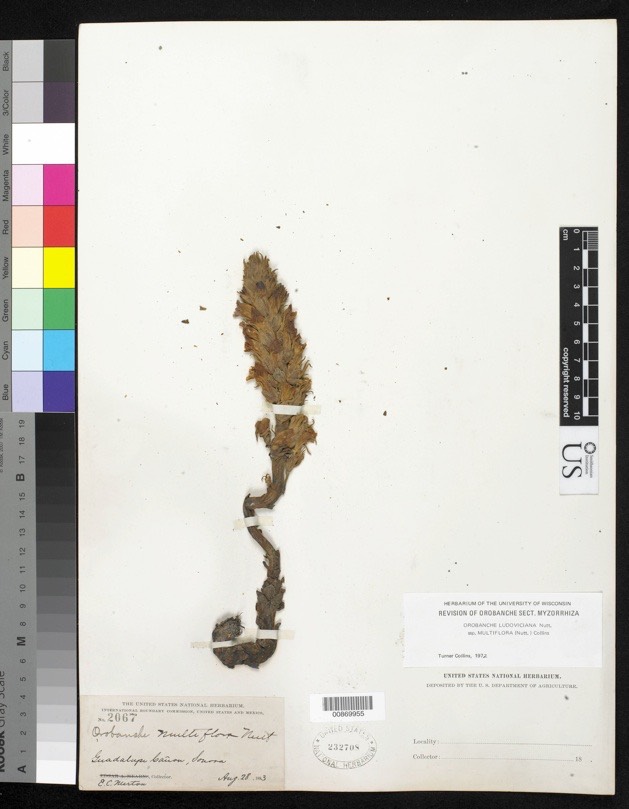

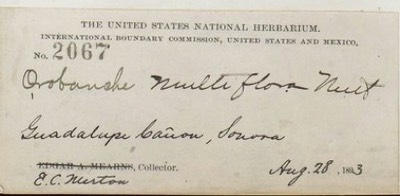

The specimen sheet shown below has a specimen collected in Sonora as part of the survey for the International Boundary Commission of the United States and Mexico, on August 28, 1893. The specimen was collected by E. C. Merton in Guadalupe Cañon (a very famous birding area). In his 1907 publication “Mammals of the Mexican Boundary of the United States”, Bulletin 56 of the Smithsonian Institution, Edgar Alexander Mearns described Ernest C. Merton’s role as “acting hospital steward. U. S. Army. Collected plants between the San Pedro River and Dog Spring (Monuments Nos. 98 to 55) from August 1 to September 23, 1893.” (p. 6 and again at p. 130) Merton is referenced in other parts of the report as well:

“On September 27, accompanied by Hospital Steward Ernest C. Merton, I rode to the forks of Cajon Bonito Creek and camped there for the night, returning to Lang’s Ranch September 28, after exploring a greater extent of the upper portion of the Cajon Bonito Valley than had hitherto been done. At this period the dreaded Apache Kid’s band of Indians was present in the neighborhood. On September 24 by men obtained the skull of a puma which had just been skinned by these Indians, the puma’s body being still warm when the soldier’s found it. Steward Merton came upon the Indian camp in a canyon on Cajon Bonito Creek on the night of September 27, but fortunately avoided observation and succeeded in reaching my camp during the night, although a severe storm was in progress and the streams swollen.” (pp. 15 - 16)

“No more were seen by me until October 3, 1893, when Hospital Steward E. C. Merton brought me another” (Colorado River Toad, Incilius alvarius, at that time described as Bufo alvarius) “that he had just caught at a spring situated between Monument No. 73 and Cajon Bonito Creek, in Sonora Mexico.” (p. 114)

To his credit, Mearns, who is a “big name” in the natural history of this region seemingly was more than willing to give credit where credit was due. Note, for instance, that Mearns’ collection sheet has Mearns name crossed out and Merton inserted.

There is little else known about Merton (that I have found). But for the willingness of Mearns to recognize the efforts of others he would be just another lost name in history.

On a personal note, the isotype specimen for the species was collected by Suksdorf at Bingen, Washington. That location is just a few miles from where I was to build my retirement home on a beautiful spot above the Klickitat River - that was the plan before the forest fire.